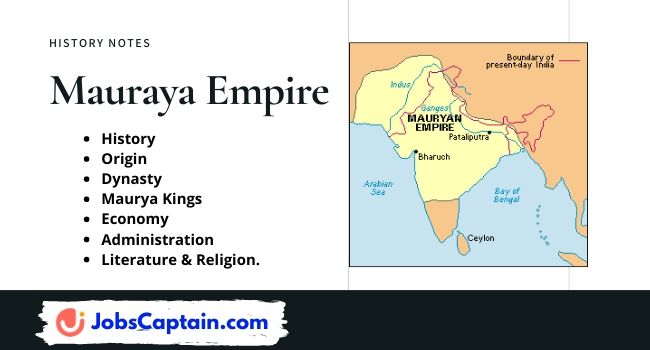

Today you will get complete knowledge about Maurya Empire’s History, Origin, Dynasty, Maurya Kings, Economy, Administration, Literature & Religion.

The Mauryan Empire was the first major empire in the history of India, ruled by Maurya dynasty from 321 BC to 185 BCE.

Let’s read History of Mauryan Empire.

History of Mauryan Empire

Chandragupta Maurya was the founder of the empire. His family is identified by some with the tribe of Moriya mentioned by Greeks. According to one tradition, the designation is derived from Mura, the mother or grandmother of Chandragupta, who was wife of a Nanda king.

Buddhist writers represent Chandragupta as a member of Kshatriya caste, belonging to the ruling clan of the little republic of Pipphalivana, lying probably between Rummindei in the Nepalese Tarai and Kasai in the Gorakhpur district.

Chandragupta is referred to as Sandrocottos in the Greek accounts.

Chandragupta was the protege of the Brahman, Kautilya or Chanakya, who was his guide and mentor, both in acquiring a throne and in keeping it.

Chandragupta met Chanakya in the forests of Vindhya. Chandragupta had been forced to flee to the forest after having offended Alexander, who had ordered for him to be killed.

The Seleucid provinces of the trans-Indus, which today would cover part of Afghanistan, were ceded to Chandragupta by Seleucus Nikator, a prefect of Alexander, in 303 B.C.

According to Jain scriptures, Chandragupta was converted to Jainism towards the end of his life and he abdicted in favour of his son and became an ascetic and passed his last days at Sravana Belgola in Mysore.

Chandragupta was succeeded by his son Bindusara in 297 B.C. To Greeks Bindusara was known as Amitrochates.

Tradition credits Bindusara with the suppression of a revolt in Taxila.

The kingdom of Kalinga (modern day Orissa), is known to have been independent during the reign of Bindusara.

A Greek named Deimachos was received as Ambassador of Greece in Bindusara’s court.

Bindusara extended Mauryan control in Deccan as far south as Mysore.

After Bindusara’s death in 272 B.C., Ashoka, one of his many sons, seized power after putting his eldest brother to death.

During Bindusara’s reign, Ashoka successively held the important viceroyalties of Taxila and Ujjain.

Ashoka is referred to as Devanampiya (the beloved of gods) Piyadassi (of amiable appearance) in inscriptions.

It was during Ashoka’s reign that Kalinga was captured and made part of the Maurya empire. The conquest of Kalinga resulted in the Maurya empire embracing the whole of non-Tamil India and a considerable portion of Afghanistan. The Mauryan empire under Ashoka stretched from the land of Yonas, Kambojas and Gandharas in the Kabul valley and some adjoining territory, to the country of the Andhras in the Godavari-Krishna basin and the district of Isila in the north of Mysore, and from Sopara and Girnar in the west to Dhauli and Jaugada in the east.

As per some traditional records, the dominions of Ashoka included the secluded hill-regions of Kashmir and Nepal, as well as plains of Pundravardhana (North Bengal) and Samatata (East Bengal). The discovery of inscriptions at Mansehra in the Hazra district, at Kalsi in the Dehradun district, at Nigali Sagar and Rummindei in the Nepalese Tarai and at Rampurva in the Champaran district of North Bengal are proofs to this.

According to the Kashmir chronicle of Kalhana, Ashoka’s favourite deity was Shiva.

The Kalinga war proved to be a turning point in Ashoka’s career. The sight of misery and bloodshed awakened in him sincere feelings of repentance and sorrow and made him evolve a policy of dharamvijaya (conquest by piety). He also got deeply influenced by Buddhist teaching and became a zealous devotee of Buddhism.

Ashoka claimed of spiritual conquest of the realms of his Hellenistic, Tamil and Ceylonese neighbours.

Hellenistic neighbours of Ashoka were: Antiochos II (Theos of Syria), Ptolemy II (Philadelphos of Egypt), Antigonos (Gonatas of Macedonia), Magas (of Cyrene) and Alexander (of Epirus).

After making a deep study of Buddhist scriptures Ashoka started undertaking Dharam-yatras (tours of morality) in course of which he visited the people of his country and instructed them on Dharma (morality and piety).

It was during the second royal tour that Ashoka visited the birthplace of Sakyamuni and that of a previous Buddha, and worshiped at these holy spots.

During Ashoka’s reign the Buddhist church underwent reorganization, with the meeting of the third Buddhist Council at Patliputra in 250 B.C.

The third Council of Buddhists was the final attempt of the more sectarian Buddhists, the Theravada school, to exclude both dissidents and innovators from the Buddhist Order. Also, it was at this Council that it was decided to send missionaries to various parts of the sub-continent and to make Buddhism an actively proselytizing religion— which in later centuries led to the propagation of Buddhism in south and east Asia.

Ashoka does not refer to the third Council of Buddhism in any of his inscriptions, indicating that he was careful to make a distinction between his personal belief in and support for Buddhism, and his duty as an emperor to remain unattached and unbiased in favour of any religion.

Within two years of his first tours, Ashoka requisitioned the services of important officials like Rajukas (district judges), Pradesikas (revenue officials) and Yuktas (clerks) to publish rescripts on morality and set out on tours every five years to give instruction in morality, as well as on ordinary business. Later, Ashoka appointed exclusive officials, styled Dharma-Mahamatras or high officers in charge of religion, to do the work. Ashoka himself undertook the tours after a gap of 10 years.

The capitals of the Ashokan pillars bear a remarkable similarity to those of Persepolis and it is believed that these might have been sculpted by craftsmen from the north-western province. The idea of making rock inscriptions seems to have come to Ashoka after hearing about those of Darius.

The Ashokan inscriptions were in local script. Those found in northwest, in the region of Peshawar, are in the Kharoshthi script (derived from Aramaic script used in Iran), near modern Kandhar, the extreme west of empire, these are in Greek and Aramaic, and elsewhere in India these are in the Brahmi script.

The inscriptions of Ashoka are of two kinds. The smaller group consists of declarations of the king as a lay Buddhist, to his church, the Buddhist Sanga. These describe his own acceptance and relationship with the Sangha. The larger group of inscriptions are known as the Major and minor Rock Edicts inscribed in rock surfaces, and the Pillar Edicts inscribed on specially erected pillars, all of which were located in places where crowds were likely to gather. These were proclamations to the public at large, explaining the idea of Dharma.

Dharma was aimed at building up an attitude of mind in which social responsibility, the behaviour of one person towards another, was considered of great relevance. It was a plea for the recognition of the dignity of man, and for humanistic spirit in the activities of the society.

Ashoka’s son Prince Mahendra visited Ceylon (modern Sri Lanka) as a Buddhist missionary and convinced the ruler of the island kingdom, Devanampiya Tissa to convert to Buddhism.

Ashoka ruled for 37 years and died in 232 B.C.

With his death, a political decline set in, and soon after the empire broke up. The Ganga valley remained under Mauryas for another 50 years. The north-western areas were lost to Bactrian Greeks by about 180 B.C.

As per the Puranic texts, the immediate successor of Ashoka was his son Kunala. The Chronicals of Kashmir, however, mention Jalauka as the son and successor.

Kunala was succeeded by his sons, one of whom, Bandhupalita, is known only in Puranas, and another, Sampadi, is mentioned by all traditional authorities. Then there was Dasratha who ruled Magadha shortly after Ashoka and has left three epigraphs in the Nagarjuni Hills in Bihar, recording the gift of caves to the Ajivikas.

The last king of the Maurya dynasty was Brihadratha, who was overthrown by his commander-in-chief, Pushyamitra, who laid the foundation of the Sunga dynasty.

The secession of Kashmir and possibly Berar from the Maurya empire is hinted at by Kalhana, the historian of Kashmir, and Kalidas, the author of the Sanskrit play, the Malavikagnimitram, respectively.

The Maurya period was the first time in Indian history that an empire extended from the Hindukush to the valleys of Godavari and Krishna.

A remarkable feature of the period was association of a prince of the blood or an allied chieftain with the titular or real head of the government, as a co-ordinate ruler. Such a prince was called yuvaraj (crown prince). This type of rule is known as dvairajya or diarchy.

The early Maurya rulers had no contact with China. Infact, China was unknown to Indian epigraphy before the Nagarjunikonda inscriptions.

The king during the Maurya period was assisted by a council of advisers styled the Parishad or the Mantri Parishad. There were also bodies of trained officials (nikaya) who looked after the ordinary affairs of the realm.

In the inscriptions of Ashoka there are references to Rajukas and Pradesikas, charged with the welfare of Janapadas or country parts and Pradesas or districts. Mahamatras were charged with the administration of cities (Nagala Viyohalaka) and sundry other matters, and a host of minor officials, including clerks (Yuta), scribes (Lipikar) and reporters (Pativedaka).

The Arthshastra refers to the highest officers as the eighteen tirthas, the chief among them were the Mantrin (chief minister), Purohit (high priest), Yuvraja (heir-apparent) and Senapati (commander-in-chief).

The head of the judiciary was the king himself, but there were special tribunals of justice, headed by Mahamatras and Rajukas.

The protection of Chandragupta Maurya was entrusted to an amazonian bodyguard of women.

The fighting forces during Chandragupta’s time were under the supervision of a governing body of thirty divided into six boards of five members each.

The chief sources of revenue were the bhaga and the bali. The bhaga was the king’s share of the produce of the soil, which was normally fixed at one-sixth, though in special cases it was raised to one-fourth or reduced to one-eighth. Bali was an extra impost levied on special tracts for the subsistence of certain officials.

Taxes on the land were collected by the Agronomoi who measured the land and superintended the irrigation works.

In urban areas the main sources of revenue were birth and death taxes, fines and tithes on sales.

Arthshastra refers to certain high revenue functionaries styled the samaharti and the sannidharti.

The most famous of the irrigation works of the early Maurya period is the Sudarshan lake of Kathiawar, constructed by Pushyagupta the Vaisya, an officer of Chandragupta Maurya, and provided with supplemental channels by the Yavanaraja Tushaspha in the days of Ashoka.

The Mauryas divided their dominions into provinces subdivided into districts called ahara, vishya and pardesh.

The secret emissaries who inquired into and superintended all that went in the empire were called pativedakas.

Varna (caste) and ashram (periods of stages of religious discipline), the two characteristic institutions of the Hindu social polity, reached a definite stage in the Maurya period.

The philosophers, the husbandmen, the herdsmen and hunters, the traders and artisans, the soldiers, the overseers and the councillors constituted the seven castes into which the population of India was divided in the days of Megasthenes.

Slavery was an established institution during the Maurya period.

Broach was a major port during the Mauryan period.

The copper coin of eighty ratis (146.4 grs) was known as Karshapana. The name was also applied to silver and gold coins, particularly in the south.

Three works, the Kautiliya Arthshastra, the Kalpasutra of Bhadrabahu and the Buddhist Katha vatthu, are attributed to personages who are said to have flourished in the Maurya period.

With the fall of the Mauryas, Indian history lost its unity for some time. Hordes of foreign barbarians poured through the northwestern gates of the country and established powerful kingdoms in Gandhara (north-west Frontier), Sakala (north-central Punjab) and other places.

In the south, the Satavahanas came to power. The founder of the family was Simuka, but the man who raised it to eminence was his son Satakarni-I.

Sometimes after the death of Satakarni-I, the Satavahana power submerged beneath a wave of Scythian invasion. But, the lost glory was restored by Gautamiputra Satkarni, who built an empire that extended from Malwa in the north to the Kanarese country in south.

Two cities of Vaijayanti (in north Kanara) and Amaravati (in the Guntur district) attained eminence in the Satavahana period.

Sri Yajana Satkarni was the last great prince of the line and after him the empire fell to pieces.

The earlier Satavahana empire had a formidable rival in the kingdom of Kalinga, which became independent after the death of Ashoka and rose to greatness under Kharavela.

In the far south of India, beyond the Venkata Hills, known as Dravida or Tamil country, three important States that came into being were Chola, Pandya and Kerala.

The Cholas occupied the present Tanjore and Trichinopoly districts and showed great military activity.

The Pandyas occupied the districts of Madura and Tinnevelly with portions of South Travancore. They excelled in trade and learning.

A Pandya king is said to have sent an embassy to the Roman empire in the first century B.C.

The political disintegration of India after the fall of Maurya empire renewed warlike activities on the part of the Greeks of Syria and Bactria.

The last known Greek king to rule any part of India was Hermaicos.

The foreign conquerors who supplanted the Greeks in north-west India belong to three main groups, namely, Saka, Pahlava or Parthian and Yue-chi or Kushan.

The Sakas were displaced from their home in Central Asia by the Yue-chi and were forced to migrate south. The territory they occupied came to be known as Sakasthana, modern Sistan.

Kanishka is attributed by many scholars to have founded the Saka era in A.D. 78. He is the only Scythian king known to have established an era. Strictly speaking, though, he was a Kushan and not a Saka.

According to Hiuen Tsang, the great empire over which Kanishka exercised his sway had its capital at Purushapura or Peshawar. His territory extended from Gandhara to Oudh and Benaras.

Kanishka is known for his patronage to the religion of Sakya-muni and his monuments.

In Buddhist history, Kanishka’s name is honoured as that of a prince who summoned a great council (fourth Buddhist Council in Srinagar) to examine the Buddhist scriptures and prepare commentaries on them.

Among the celebrities who graced Kanishka’s court was Asvaghosha, a philosopher, poet and dramatist, who wrote the Buddha Charita.

Kanishka’s rule lasted 23 years. His immediate successor was Vasishka, followed by Huvishka.

Mathura became the great center of Kushan power under Huvishka.

Huvishka’s empire was spread further west, till Wardak to the west of Kabul.

The last great Kushan king was Vasudeva-I.

The decline of Kushan power in the northwest was hastened by the rise of the Sassanian dynasty in Persia.

The Kerala country embraced Malabar, Cochin, and North Travancore.

Thank you for reading about Mauryan Empire. Read here more about Indian History.

important notes on Mauraya Empire History.